In the blog post about my work as a volunteer teacher, I referred to Daniel Le Gal’s article English Language Teaching in Colombia: A Necessary Paradigm Shift. What immediately caught my attention was that the author mentioned coursebooks designed specifically for Colombian students. One of them is English, please!, which was created by the Ministry of National Education in collaboration with the British Council and Richmond ELT. Its latest edition can be downloaded for free from this page, so I think that we should take a closer look at it.

The series comprises three coursebooks aimed at students in the 9th, 10th, and 11th grade who have been studying English without making any progress. I work in the private sector and my students often complain about the level of English instruction in public schools. Adriana González wrote about this topic in English and English teaching in Colombia: Tensions and possibilities in the expanding circle, which I recommend reading in case you are interested in teaching English in Colombia. It would be harsh to blame teachers for the situation because it seems to be a systemic issue. English, please! is part of the government’s strategy to address that.

What you will notice right away is the fact that the coursebooks use British English. That is to be expected when the British Council is involved, but is that the right option for the students? In 2019, Colombia was visited by 4.5 million foreigners, and 22% of them were from the USA. Visitors from the UK didn’t even make the top 10, so they don’t appear in the government’s report. The country is geographically and culturally much closer to the USA, yet English, please! teaches Colombian students to use at weekends and a torch instead of the equivalents that are more common in the US variety of English.

In fact, in spite of writing my blog posts in British English, I actually use the US spelling and talk about soccer when I teach Colombian students because they are more familiar with it. I also point out differences between the two varieties of English when necessary. English, please! simply promotes the British one even though I think most Colombian teenagers would probably find learning American English more relevant to their needs and interests.

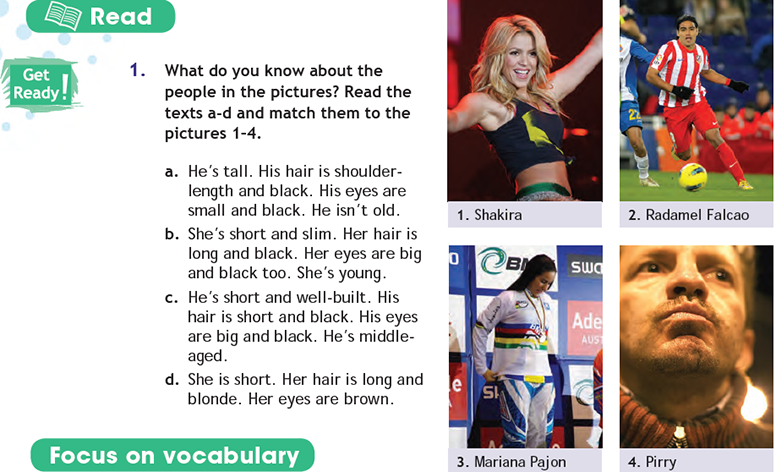

Fortunately, the coursebooks avoid the pitfalls of including content about random British celebrities. English, please! gives the students an opportunity to learn English while reading about Colombian food, places, people, etc. There is some international content referring to other parts of the world, but in general I can imagine the coursebook making the learning experience more personalised and engaging. It doesn’t always work perfectly well, though. Let’s take a look at the following example:

The coursebooks were written by a team of Colombian ELT professionals and international freelancers. I guess the person responsible for this part isn’t a football fan. Falcao is a good player, but I certainly wouldn’t call him tall because in every game there are several teammates and opponents towering above him. In addition, the photo of the other guy isn’t great and you can’t properly see what colour his hair is. I think that they should have chosen something better than an image downloaded from Wikipedia.

To be honest, I think the first book, which is supposed to be used with 9th graders, is the weakest one from the series. I think some parts could have been done in a slightly different way. For example, this is how students whose English is at a low level are encouraged to improve their listening skills in the first lesson:

English, please! contains glossaries with words and lexical chunks translated into Spanish. I suppose this is based on the fact that the books are expected to be used in a monolingual environment, so it’s not a completely bad idea. I’d still prefer to use dictionaries because I find them more helpful than word-for-word translation. There is also some strange stuff in the first coursebook. I wouldn’t call myself an expert in the Spanish language, but this explanation of special cause doesn’t seem right:

The good news is that the following two books are considerably better. There are a lot of opportunities for collaborative work, and I imagine that students will enjoy doing some of the tasks. The texts about Colombia aren’t bad either. It was also quite interesting to see that the writers decided not to avoid PARSNIP topics. The following activity is from the last book, which is meant to be used with students older than 16:

There are no surprises when it comes to the linguistic content because English, please! follows the traditional synthetic syllabus. It contains the same ‘building blocks’ of language that you will find if you pick up any run-of-the-mill coursebook, and I think that it’s necessary to supplement it with other activities and materials. Its main advantage is that it deals with topics that Colombian students are familiar with, so the teacher doesn’t need to spend a lot of time on personalising the coursebook content.

I’d say that English, please! is a nice attempt to come up with something more appropriate for the local market. It isn’t perfect, but using this series makes more sense than teaching completely random topics from a book designed without any specific target audience in mind. I just don’t think that coursebooks are the main issue in ELT in Colombia. Teachers who have received relevant training will deliver amazing lessons even when they are asked to use a terrible coursebook because they will adapt the activities or abandon most of the book and design their own materials. Of course, if local teachers’ training consists mainly of being taught about language, then even the best coursebook in the world won’t be very useful.

This series also contains something I haven’t seen in any other publication of this type. If you open this PDF file and go to page 2, you will encounter an interesting name there. I mean, his English is great, but I wonder why this man is listed on the credits page of a coursebook for high school students. Any ideas?

► If you enjoyed this blog post, I recommend that you read More Than a Gap Year Adventure, a collaborative book aimed at those who wish to have a long-term career in our profession.